Freedom sure sounds great, doesn’t it? It inspires whole convoys, after all. There is an entire American congressional caucus dedicated to it! We’re supposed to let it ring, and for that privilege, we are charged a buck-oh-five. There are statues dedicated to the very notion of liberty, and yet it remains vague and undetermined, generally on purpose by those advocating for it. Typically ‘Freedom’ in the political sphere means rich people not having to pay any taxes, but that’s never explicit, and so people often have this vague, fuzzy feeling about the term that’s generally positive. So what does freedom actually entail? Is it more than just feeling secure against the threat of terrorists and commies through lower corporate tax rates?

Freedom, when pressed, is obviously about the freedom to choose. We can’t choose anything if Sharia Law is enforced and we all have to convert to Islam, or the communists have us all wearing the same grey sweatsuit lining up for the same loaves of bread. Freedom means being able to choose between loaves of bread and the freedom to convert to Christianity!! Right? To an extent. Freedom in its most absolute sense would be all the choices from choosing between two loaves of bread to killing yourself. If we are truly free, there are an infinite number of choices available to us at any given moment.

Does this sound terrifying? It should! The freest person in the world is the recovering drug addict. Their entire lives were previously dedicated to all aspects of doing drugs: grinding to get the drugs, doing the drugs, a short grace period to do some wallowing, and then grinding again. It’s a loop that’s hard to escape, but it does happen. When it does, that person has only known a very constrained lifestyle, and now, without any of it, they are free to do literally whatever they want. Maybe they might go back to school, or start working again, or reconnect with their sober friends. Or maybe they might travel, or go to a treatment centre, or move to a new home away from their drug den, or go for a walk or a movie or the library or the mall or a drop-in centre or a counseling session or a swim in the ocean or a music festival or back home to their parents or a cry in the shower or, as has been established, just end it all. These are choices that must be made every second of every day without any idea of when this flood of choice will end. People off themselves all the time in recovery, and part of the reason is the amount of freedom that they have. The experience of absolute freedom is a void of unknown and infinite possibility, an expanse of overwhelming nothingness ahead of you, and you are the only person responsible and capable for taking that desolate void, both outside and inside of yourself, and turning it into a worthwhile life. Alcoholics Anonymous tells recovering addicts to take things one day at a time simply to limit the number of choices people in this precarious and vulnerable position have to make. The existential anxiety of making a choice is so great that many people relapse simply because the miserable cycle of drug use is at least a known quantity and has a degree of comfort in taking those choices away. Anyone calling them a coward for this has never undergone the experience.

Limiting freedom is actually quite healthy for normies too! You ever hear of structure and routine? They’re great ways to stay healthy. People have a hard time making it to the gym when they have to choose to go to the gym, but when it becomes habit, and they are no longer actually choosing to go, they now have a routine. This is actually incredibly beneficial! If someone is feeling low and unable to do much, their bodies will automatically follow the routine they’ve habituated, and voila! They’ve still made it to the gym despite their blues, and you know what? They’re probably feeling a bit better because of it. Obviously the reverse is true with bad habits, but creating a good life is about creating good and healthy habits. Even something like making a list is helpful because it forces our decisions into a box that restricts our choices to the items listed – they get done because we don’t allow ourselves to choose outside of that box. The irony of freedom’s celebrity is that the goal of life is reduce the number of choices we actually have to make on a day-to-day basis; we just automatically make lunch for work the next day, or go to bed at a reasonable hour, or use the healthy groceries that we buy rather than leave them to rot in our refrigerators. Success comes when our lives are mostly automated, and an automated lifestyle is not a free one.

This seems somewhat intuitive. Has anyone faced a major life choice and thought: wow, this is a pleasurable experience! Or was there a lot of anxiety and catastrophizing about what the future might look like whether you choose this or that? Especially once you realize that not making a choice is also a choice, and allowing the status quo to perpetuate itself is one of those infinite choices you have to deal with. If a choice seems easy, it’s likely because you’ve been culturally primed to accept that choice as typical and normal – and how free is that of a choice, really? Jean-Paul Sartre, notorious philosopher of freedom, tells us we are “condemned to freedom.’ Choosing negates all other possible choices, and is a terrifying, inescapable, and necessary experience.

And I do think it’s necessary! Don’t get me wrong: I’m not against freedom! We must choose. Having someone else making these major choices for us is an unforgiveable oppression. Just, as with everything, in healthy moderation. Even those Freedom Truckers wore their seatbelts on their drive to Ottawa, and had nothing to say about seatbelt mandates, or traffic light mandates, or pants mandates. No one was out there protesting their freedom to not wear pants, only masks, even though the arguments against pants are way more grounded in science than the arguments against masks!

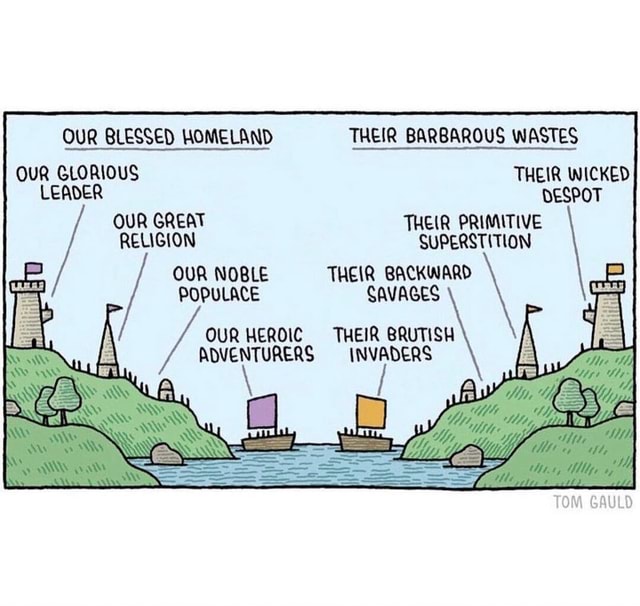

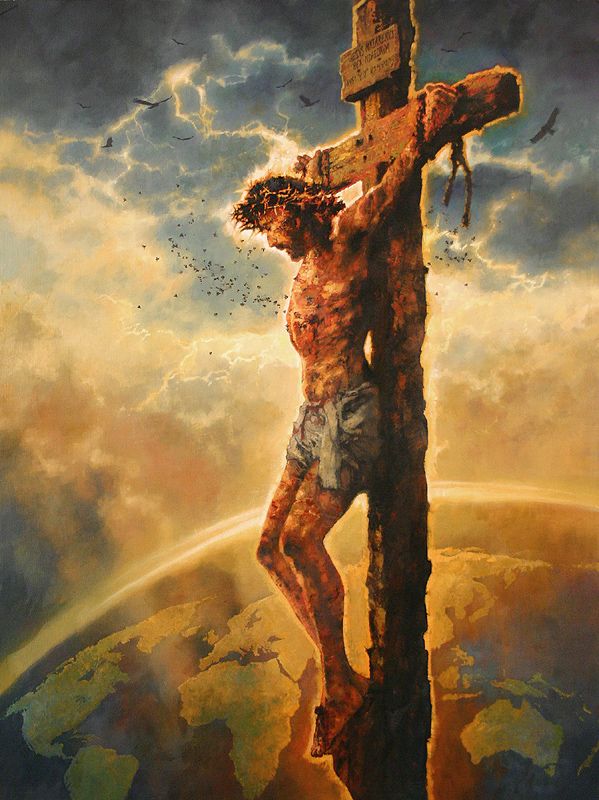

So why is freedom, something that actually kinda sucks, celebrated like it’s the fundamental aspect of Western civilization? I mean, I think it’s reasonable to yadda, yadda, yadda over the escape from the tyranny of the British monarchy since the freedom I’m describing goes well beyond the fight for democracy, but I think the Freedom of today has far evolved beyond that democratic rebellion oh so many centuries ago. Given the link between the fascistic elements of Western society and claims of Freedom, I think that much is clear! So what is it? My personal thoughts are that Freedom has come to represent the dream of a meritocracy. We obviously aren’t living in a meritocracy, but if we are Free, then we must be! I earned my life through the choices I’ve made, and if there are outside social factors subtly influencing my position in life, then the value of my merit is lessened. If I am Free, I am not determined. Whether my life is good or bad, it is my own. I have carved out my place in this world, and the only way that that’s going to change is if the commies and terrorists are allowed to come take our Freedoms away. When people talk about Freedom, they aren’t actually talking about freedom at all since, as discussed, freedom is an incredible burden foisted upon us by an uncaring universe. They’re talking about dignity. I matter because I am Free. Their vitriolic shouts of Freedom and spittle aren’t a call for action, but a plea to have the meaning of their actions recognized.

Freedom is a good thing in the same way that democracy and socialism are good things; we ought to have a choice in our governments and our workplaces. We ought to have choices in our own lives even as we aspire to limit them. Those choices can be painful, and an overwhelming amount of freedom is such a sublime threat that I pray none of you ever have to face that kind of dread. Freedom is… fine, I guess. We’ve become kinda weird about it, but that’s because society has become kinda weird. We’ve become so disconnected from the world around us that we actually insist on it now; if the world is connected to me in any way, then what I do doesn’t matter! How broken of a culture is that? Freedom with a capital F has seemingly become the last bastion of being okay with ourselves while all other forms of meaning are being erased by those who profit off our existential despair. This is why Freedom and fascism can exist in tandem. The thing is though, we can create our own meaning without having to believe that we are alone in creating it. Being alone sucks, but being free around other people means respecting their freedom which often means limiting our own. Given we’ve established that limiting our freedom can be a good thing generally, this shouldn’t be seen as a threat, but as a way to lead a happier, healthier, and more cohesive lifestyle.

Freedom is like eating our vegetables. We don’t want to do it, but we have to, and if we can find a way to make them more appealing by dousing them in the ranch dressing of moderation, that’s probably for the best. What we don’t want is for Freedom to distract us from the reality of freedom. Freedom more often than not needs to be limited, whether that’s to avoid existential dread, to have a healthy routine, or simply to get along well with others. This doesn’t eliminate meaning, but enhances it. Freedom with a capital F is a lie. Freedom with a lower case f is all we have, all we are condemned to endure. Best to make the most of it!