I am a social worker in Canada, and with some frequency I am told that I work in a noble profession. And it’s always that word, too: noble. Social workers are paragons of virtue simply by dint of how we make a paycheck. We don’t toil monotonous labour; we don’t exploit those same labourers for surplus value – we transcend the capitalist dichotomy. Doctors, firefighters, and the like may be heroes, but social workers are noble. We’re not glamourously saving lives; we’re in the trenches helping the less fortunate. We sit among both the lepers and the crooks. It’s unclear what we actually do, as I find when talking to even those who work intimately with social workers, but our virtue is assumed – whatever it is we’re doing with those lepers and crooks is irrelevant. Our proximity to pain is enough.

So what do social workers do? Are we really so noble? Am I secretly a monster??

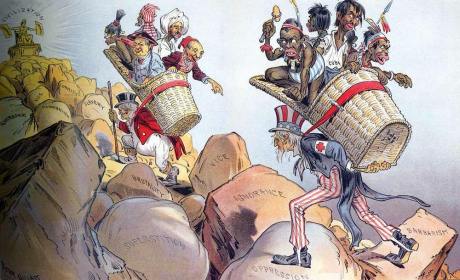

The Sixties Scoop refers to direct policies of colonial Canada to remove indigenous children from their homes and place them into white foster families or fully adopt them into other, equally white families. It ran from about the 1950s until the 1990s. It represented a shift in approach from the residential school policy which was established to follow the maxim, “Kill the Indian, save the man.” This approach aimed to “save” the indigenous person by “killing” everything that was indigenous about them, and the residential school program aimed to do exactly that by removing children from their families and culture, abusing them if they spoke their native tongue, and presenting them as superficially white with shorn hair and new clothes.

As abducting children from their homes and imprisoning them in abusive facilities became more and more gauche, the Canadian government needed a new methodology to “save” them. In comes the social worker to investigate indigenous homes, and when the indigenous parents are found lacking by white colonial standards, abducting the children from their homes and imprisoning them in abusive white families. This practice continues to this day in what’s called the Millennium Scoop, as the majority of youth in care across the country remain indigenous despite being a small fraction of the Canadian population. Social workers as a profession are responsible for this.

But surely social workers must do more than whisk babies away in the dead of the night to feed the endlessly hungry maw of settler colonialism! And we do! Socials workers are in schools, healthcare, all over the place. We even do more than just report new moms to child welfare when they’ve given birth while poor! We also connect those without an income to regular, adult person welfare which in British Columbia adds up to… $560 a month.

Now, I know what you’re thinking: that seems like less than table scraps. But there’s more! Social workers can also support low-income people in getting housing that is arguably worse than homelessness: insufficient temperature controls that have residents freezing during the winter and cooking in the summer; illegal practices by landlords including unlawful evictions; restrictions on guests preventing loved ones from ever visiting; health issues arising from mold, bed bugs, vermin, and general lack of upkeep; the list goes on. Those helped by social workers can enjoy their fraction of a scrap living in deplorable squalor.

The resources that social workers can actually provide to the people they’re “helping” are so insufficient it seems somewhat surreal to refer to it as helping at all. This is the parsimonious bounty the system provides, and social workers are the smiling face of the miser doling it out. People don’t typically know what social workers do because even in the best case scenario, the real answer is so close to “nothing” that we would all collectively die of embarrassment if anyone actually looked into it.

If our jobs are so trivial, how did we become noble? In this instance, it’s useful to look at the etymology of the term. Noble comes from the Latin nobilis, referring to the high-born families of the time: the nobility, duh! It is a moral framework steeped in hierarchy. Noble people are those who embody the ethic of the aristocracy, and social workers do exactly that.

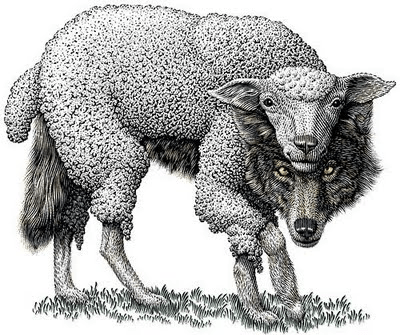

The idea of the welfare state is to help the less fortunate, but capitalism can’t actually address any of the root causes of poverty and inequality because that would upend capitalism itself. Welfare is the compassion of capitalism whose sole purpose is to never solve anything. Monetary policy requires a percentage of the population to be unemployed; when there is inflation, the central bank raises interest rates in order to produce more poor people. Our system requires poverty, and if any of the methods utilized by that system ever did anything to address it, society would collapse into itself in a Dadaist paradox. Social workers are the systemic representation of that compassionate farce. We are noble because we are the morality of the capitalist elite. When approaching indigenous population, we are the ethic of the white settlers, taking up the white man’s burden to serve our captives’ need. We ease the worries of an otherwise apathetic middle-class, comforted knowing that social workers are there as a bulwark against the cognitive dissonance from class and racial guilt.

We are not, however, a moral profession. As compassionate and as genuine as social workers tend to be, our “help” is often harm. Indigenous families do not look upon social workers as saviours but as destroyers, tearing up their families in the name of an oppressive fantasy of “doing good.” The impoverished do not see social workers as angels coming down from on high, but merely as a means of drowning less quickly. We try to be good, but good on whose terms? We try to help, but we’re in denial, cogs maintaining the facade of a benevolent state. True solutions would not involve social workers at all, but a restructuring of the world so that the horrifying outcomes of colonial capitalism would not be produced in the first place.

If the ethic of nobility is the delusion social workers use to sleep at night, it is useful to look at the Latin once more to try to break free from that corrupted reverie. We traditionally think of the vulgar as the offensive, the crass, the unclean. In its origin, however, it referred to the low-born, everyone else outside of the nobility. These are the people social workers are supposed to support, yet we remain detached and aloof. How can we bridge that gap? What would an ethic of the vulgar look like? What would social work practice look like if it embraced the vulgar instead of the noble?