Virtue ethics are one of the oldest established ethical systems in the West. They gave the ancient Greeks traits to try to embody and paragons to try to emulate. Aristotle came up with a list of virtues with the intention of giving people a guide on how to live life successfully. Not a step-by-step instruction, but more of an encouragement toward a better way of living. It is this striving that creates the good life, the eudaimonia, where we live in flourishing happiness. We are at our best in our active virtue in the way that a horse is at its best while running, for just as the purpose of the horse is its speed, so too the purpose of a human is to live virtuously. Virtue is what we aim for, what we strive for, and in that striving, we are living well.

Being virtuous, according to Aristotle, is found within the golden mean. The best life is lived in moderation – neither to be rash nor cowardly, we should live firmly and courageously. Neither miserly nor prodigally, we should live charitably and generously. Aristotle produced a list of virtues within this golden mean as the foundational structure upon which our eudaemonic life can be built. The happy, flourishing life is one of acting honestly, patiently, modestly, and friendly.

To become virtuous, one must obviously learn how. Virtue is a skill. One is not born patient, as anyone exposed to a child will discover. Virtues are imbued into the individual by the sage, the one who has achieved their good life. It is up to society to produce its sages so that virtue can be passed on from one generation to the next. The purpose of life is to lead a good one, and so ideally we would want a culture that aims to socialize its young toward virtue.

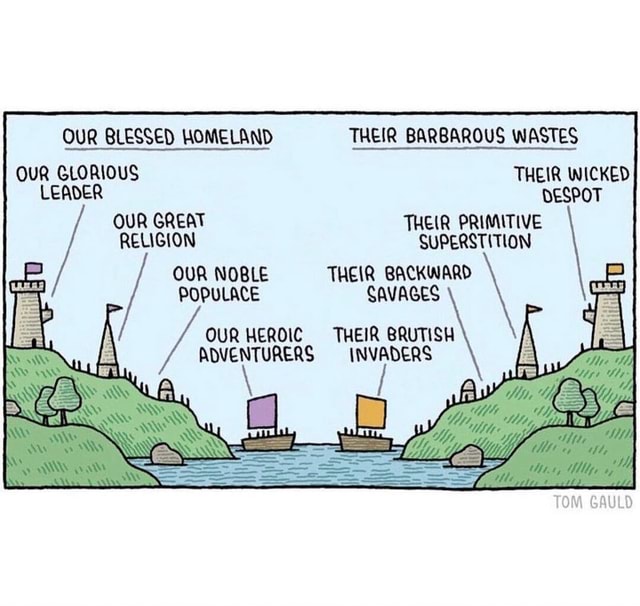

The problem with virtue ethics is that we always do by default. Children will be socialized and taught how to be virtuous according to the culture that surrounds them; it’s just that those virtues will differ from culture to culture. Christian culture encourages the virtues of forgiveness and mercy whereas a Buddhist culture would focus on the serenity required to relinquish attachments. Who we see as our sage determines the virtues toward which we aspire, whether the Buddha or the Christ.

Despite the persistence of religion, these sages of yore are no longer as influential as they once were. You might have been able to guess this by your having previously scoffed at Christian culture being described as forgiving. This is because we have abandoned those cultures, if not in name then at least in practice. Today, our culture is one of capitalism. Our sage is the billionaire.

Perhaps you are unswayed by my assertion. However, people write books about how to become wealthy, encouraging particular behaviours that will surely lead to financial success. There are schemes, podcasts, cults, and conferences. Television has created an entire genre of entertainment where people go to absurd lengths to become wealthy, and fixates on the traits of the winners as the key to their success. Each of these methods demand a certain “type” of person if that person wants to succeed. If you stay poor, it’s because you just didn’t inhabit the virtues of the wealthy.

A quick Google search turns up a myriad of numbered lists providing the Top Habits of Billionaires. The wealthy set goals and follow them with single-minded determination; they dream big without fear of failure; they spend their time learning and surrounding themselves with people smarter than they are; they take care of themselves by eating and sleeping right; and finally, of course, they are cautious with their money. One could easily turn this into a list of virtues similar to that of Aristotle. The billionaire sage is focused, driven, prudent, curious, social, and bold. Many of these could even exist in alignment with those of Aristotle.

The thing is, the virtue ethics of the Ancient Greeks was self-fulfilling. Living well is its own reward. Hence why moderation is important, even in our virtue. There is no such restraint within capitalism, however, because the goal isn’t virtue in-itself: it’s money. There is no moderation in the virtues of today because capitalism necessitates infinite growth. The concept of the golden mean is antithetical to the voraciousness of the capitalistic system. Today, one is virtuous for the sake of something outside of virtue, which means that the virtues themselves are only of secondary value. The “Hustle Culture” and “Grind Culture” that have sprung up as the pinnacle of these modern day virtues is toxic for exactly this reason. It is physically and mentally exhausting to live this “good life” because the demands put on us aren’t driven by any idea of a eudaemonia but by what was once considered a cardinal vice: avarice.

The other problem with capitalistic virtue ethics is that they’re a lie. Social mobility has little to do with one’s virtue. The ability to actually improve your financial situation is low, and has been getting worse for decades. Wages are going down, so we’re making less money than our parents. The only place where incomes are rising are for those who are already rich. The decline of unions, the change in technologies, barriers on education… these are the things that are keeping most of us broke, not our personal vices. No matter how early you get up or the number of goals you set, your economic situation probably isn’t going to change all that dramatically.

A society will necessarily create its own virtues. Societies are created by humans, and humans need to know how to behave well to fit in with their neighbours. We will always have virtues, and we will always have sages. However, it is important to observe what those virtues demand of their adherents, or if living like the sage actually allows one to become like them. The modern virtue ethics of capitalism are viciously idolatrous in both regards. The Renaissance was in many ways a return to antiquity to absolve Europe from the hollowness of the medieval period. With capitalism, our virtues are equally hollow. While I am not so nostalgic to demand a return to the Ancients, it is at least clear that our current virtues leave much to be desired.