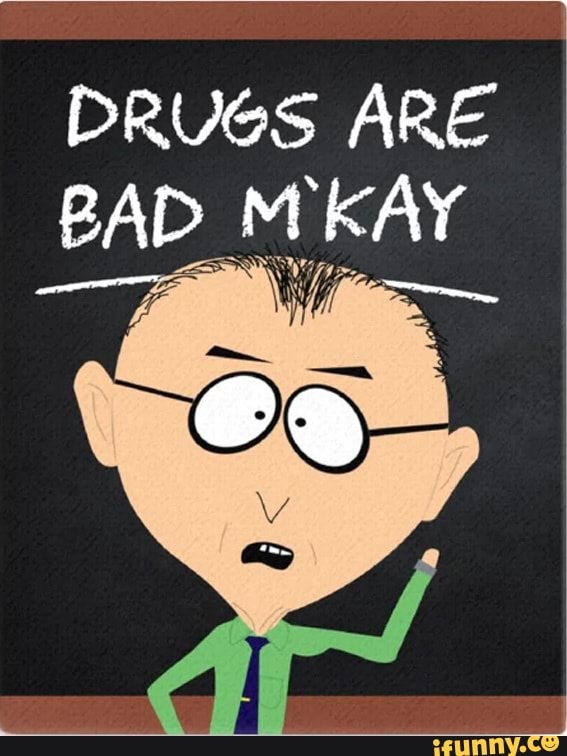

Vancouver is Dying starts with a threat to its viewers. You are not safe; every day there is a statistically improbable risk that you will be assaulted by a stranger. The cops have been castrated by woke mandates to avoid overt brutality, and so the city has run amok. There are no consequences to the choices people make, so we mourn the passing of a once great city. The reason for all of this… is drugs. Not poverty; not the civil disenfranchisement of a particular neighbourhood; not the modern cumulation of centuries of colonialism. It’s drugs. Possibly woke-ism too, since the defecator of this trash, Aaron Gunn, literally says that the Left believes opiates are a good thing, but he focuses on drugs as the root of Vancouver’s degeneration. Drugs, we are told, are bad.

Despite being the alleged cause of everything evil that’s happening in Vancouver, Gunn doesn’t actually spend all that much time talking about them. What is a drug? Alcohol has been shown to be the most destructive addictive substance, but I guess alcohol is irrelevant to the Downtown Eastside (it’s not). Both sugar and caffeine hit the same dopamine receptors in your brain as crystal meth, but those also don’t count (how many people reading this rely on caffeine to enable their daily functioning?). We can also safely ignore process addictions too, like gambling and video games. When Gunn talks about drugs, he only means the highly unregulated ones, the ones they don’t advertise on TV. Seeing the harms of addiction in a wider context of mass consumerism might lead to… a criticism of capitalism! And we can’t have that.

So of course Gunn avoids that context to the best of his ability. In the few brief interactions he has with active drug users, he asks one what she thinks about addiction. She brushes off the harms that everyone already knows about with street drugs to talk about global addictions, like the equally suicidal addiction humanity has with oil and gas, or the addiction to money in the financial markets, or the addiction to consumer goods we might indulge in after losing our life’s purpose during a midlife crisis. Rather than discuss the threads linking micro and macro addiction, Gunn says, behind her back, that she must be in denial. She didn’t deny that her drug use was harmful; she just wanted to talk about the context as to why all of these problems exist, and Gunn absolutely does not. So he calls her delusional without giving her an opportunity to respond – but who cares; she’s just a supid junkie, right?

According to Gunn, addiction is a silo that only impacts a ‘certain type’ of person, and isn’t connected at all to the culture or global habits surrounding it. So where does it come from? Why do people use drugs? Drugs seem kind of bad, so how come so many Vancouverites… sorry, people specifically in the DTES and nowhere else… how come they do the drugs? Par for the course, Gunn doesn’t really explain. He makes one inference, and expects the viewer to figure it out for themselves.

The closest Gunn comes to explaining where drug use comes from is by talking about the choices that some homeless people make to stay in the street. Our old friend Colonel Quaritch has the unmitigated gall to suggest that it’s easy to get housing in Vancouver (as a social worker, I found this to be particularly offensive), and Gunn doubles down on this by showing that there has been 1,400 new supportive housing built over the past four years, with 350 new ones being built. Of course, those 1,400 are already full (the waitlist for supportive housing is a couple of years), and there are an additional 2,000 homeless people that need help, so his optimism is… misplaced. We can also combine his bullshit with another ignored statistic that about 7,000 housing units are in need of replacement, and we can see that the rumours about the challenge of housing in Vancouver are in fact true. Turns out it is expensive and difficult to find housing in Vancouver! Who could have guessed!?

Okay that rant was mostly for my own benefit, but let’s return to Gunn. He wants to show that the chaos is a choice – that the option for stability is there for those who want it, but that people live in squalor and disease because… they’re crazy, I guess? A DTES resident tells him that people sometimes choose to live in the streets because of the restrictions in a lot of the supportive housing units, and then that’s enough for him. No point in exploring what those restrictions might be, or what the benefits of the streets might be otherwise, just enough that we have captured a DTES “resident” confirming what we already know. People who use drugs are just completely irrational.

It turns out though, that even people who use drugs are rational in their choices – they are just too often limited in the choices they can make. If a drug user has a choice between using drugs in such a way that it is likely to kill them, or to use drugs in a way that is likely to not, they’re going to choose the way that allows them to avoid death. Rational! Same thing with homelessness. If we talk to people who do choose that lifestyle, they are often fleeing violence that is pervasive in shelters and some SROs, or they want to live in a community of mutual aid amongst their peers without officious oversight. The restrictions that Gunn avoids talking about are typically restrictions on visitors, meaning that your loved ones aren’t allowed to visit. This means you essentially can’t have a partner or children or friends. If I foreshadow a bit that the opposite of addiction is connection, then we can see that these restrictions would actually encourage drug use rather than help eliminate it. It would be rational for someone to choose their loved ones over rat/lice/bedbug/cockroach infested housing, wouldn’t it? Gunn even acknowledges that a lot of the housing is awful, that it’s filled with drug dealers and drug users, but then seems vindicated in degrading homeless people when he’s able to confirm that people don’t want to live there because of that very awfulness. He doesn’t offer a clarion call for better housing in more suburban neighbourhoods where people might escape violence, addiction, and poverty because presumably that would entail the spread of their disease into the ‘purer’ neighbourhoods.

If people don’t use drugs because they’re just cuckoo-bananapants, then why? It’s a question that should have been at the forefront of anything trying to be a documentary about drugs.

The secret they don’t tell you about drugs is that they’re not actually bad. Drugs are amazing. You’ve likely at least had sugar, caffeine, and alcohol, and most people have a lot of fun with those things! The trouble with drugs isn’t that they’re so amazing that they become addictive, it’s that they’re a problem for those people whose lives are so awful, so that when they do take drugs, their amazing-ness brings them to about normal. Heroin feels like a warm, loving hug; imagine what that must be like for someone who has never felt a secure connection. The first experience of drugs that people who often become addicted is usually, “this must be what everyone else feels like all of the time!”

Addiction typically begins around adolescence when teenagers are supposed to be learning how to cope with complex emotions, and if someone with a lot of complex emotions learns that drugs are an incredibly effective way at dealing with them, that’s how they learn. Just like it’s hard to learn a new language once our first becomes so ingrained into our way of navigating the world, so too is it a challenge to learn a new way to process our emotions once we’ve already established something that works. The physical dependence of drugs can be overcome in a few days, and for drugs like crystal meth, you literally just sleep it off and then you’re done. The psychological dependence, the need to numb yourself from all those accumulated feelings, that’s what causes relapse. You may have heard that an addiction is a behaviour that continues despite negative consequences; well, the negative consequences of not using are often worse. Feeling decades of trauma all at once when the drugs wear off is more often than not still worse than any infected absess. Drugs are not the problem of addiction. It’s just that people with addiction have drugs as their only workable solution to help them cope with what they’re going through, and it’s hard to learn other ways – particularly when drugs work so well and so quickly. Some call addiction a learning disorder rather than a disease for this very reason.

Rat Park is an experiment that sought to question the original idea of addiction. We once understood addiction as absolute – a rat was put in a cage, and had two options: a regular water, and water laced with cocaine. Those rats consistently chose the cocaine water until they died. Rat park was an alternative: rats were put in a cage with tubes and balls and other fun rat activities and, most importantly, with other rats. The two water options were the same, but these rats only had the cocaine water every once in a while. The rats lived full and healthy lives, and occasionally got to have wild parties when they opted to go for the cocaine water. Remarkably, rats from the first cage could be put into Rat Park, and they would lose their addiction relatively quickly. To sum up, it’s never been about the drugs, but about the lives of the people who use them.

What if we understand addiction as a response to something rather than the problem itself? Looking at process addictions and less stereotyped substances might become relevant to our thesis. Global patterns that impact culture might contribute to the so-called disease. If we are told to always be consuming more and more to avoid loneliness, grief, to find meaning, then perhaps a comparison to a midlife crisis sports car is actually quite apt, and it is Gunn that is actually the one in denial. What is addiction a response to? If it is getting worse, what is going on in the world that is exacerbating it? I guess if we never ask what addiction or drugs are, then we avoid that pesky subject entirely.

Drugs start out as the rational choice to cope with childhood trauma, to the point where drugs can even save someone from suicide. That becomes their only method of coping, and then they become stuck in that lifestyle even past the point when its consequences start to outweigh its benefits. Ending drug use is only ever really an option if the person has meaningful activities and connection waiting for them on the other side, in an environment stable enough to maintain it. Do police and jail sound like the optimal environment to provide that? Is Gunn right that we should be bullying people into quitting drugs? Or should we recognize that a sober lifestyle just isn’t a reasonable option for a lot of people given their circumstances within capitalism, and do our best to support them in the world they’re stuck with, recognizing and respecting their rational choice in opting to live this way? Perhaps we could make sure that the drugs they take don’t kill them, since they’re human beings still worthy of dignity, perhaps more worthy given the wars they’ve lived through.

Fuck them, says Gunn. They will live and die as he decrees. Join us next time, when Aaron Gunn will try to suggest that having more harm for people who have endured so much already is a good thing actually.