The Todd Phillips Joker-verse and HBO’s The Penguin create their respective monsters out of very similar clay. The world is unfair: society is heavily stratified, inequality is high, and the odds of transcending the hell of your poverty are grotesque – or laughable, depending on your rogue. These two pieces of entertainment understand the tragedy of modernity, and portray us with depressing accuracy. Our world is dying, and the thoughts of too many are perseverating only on how to profit off our deaths. We vulgar plebeians are damned, cogs in the machine generating our own demise. The West and its contradictions are primed for villainy, and there is no Batman to crash through the sky light. No one is coming to save us. How these two DC antagonists are manifested in their barely-fictional worlds is probably one of the better lenses to understand the monsters in our own.

The Joker begins his foray into villainy in a way that I’m fairly confident was not intended by the creators of the film. Arthur Fleck is a man struggling in poverty, loneliness, and despair. He has a shitty job and worse prospects. His arc culminates in violent anarchism, rebelling in fury against his condition. Arthur lashes out as The Joker against an elite that has only ever looked down on him, smug in the certainty of their position as arbiters of the structures of the world; banker bullies whose material success has come at Arthur’s expense, and Murray Franklin, the talk-show media figure who laughs at and degrades him.

In short, this is Trump’s story of America. The establishment has taken advantage of you; liberal elites look down their noses at you, laugh at you. Any kind of systemic reform is secondary to simply turning it all to ashes. As an Alfred once said, “Some men just want to see the world burn.” Arthur Fleck is representative of the so-called Basket of Deplorables who are judged by the mainstream, and this is their response to it: fuck you. The only reason that I’m confident that the creators didn’t intend to celebrate Trumpism’s bloody revolution is that Arthur is an unreliable narrator, and the scenes that consistently show his delusions are the ones in which he’s connected to others, where he’s loved. The devoted crowd cheering at Joker’s murderous performance is not real. I believe the original intention of Joker was not to valorize a Trumpian antihero, but to show and empathize with the unhinged mind of a school shooter. Joker is canonically a villain. The appropriate response to a broken world is to fix it, not to break with it. Somehow that villainy was missed, and my interpretation has not been the popular response to the film. A sequel was required.

Joker: Folie à Deux has been universally panned, and for good reason. It’s a bad movie! But also for very bad reasons because some people seem to think that it is a rejection of the first film, and that’s simply not true. Arthur as a character rejects the lessons of the first film, but it’s ambiguous if the film does so as well. The second film canonizes the celebratory mob at the end of the first film as real, and, fine. Sure. Arthur gets caught up in the fantasy of his own greatness in response, but ultimately rejects that fantasy because he recognizes that his homicidal approach was incredibly traumatizing to his only friend, Gary Puddles. Joker isn’t a revolutionary, he’s a bully too. His approach to the broken world is to embrace what broke it in the first place: cruelty, degradation, and all of it at the expense of vulnerable populations. It’s this insight that enlightens Arthur to the meaninglessness of his crusade, that he is reinforcing the harms of society rather than rebelling against them. But being the Joker is out of his hands now. His corruption had already infected the populace, and Joker’s revolution continues without him. Viewers are confused that perhaps the minor character Ricky was supposed to be the canonical Joker all along, but in truth, all of the clowns dressed in their makeup who blow up the court house are the Joker. His ideology has won, even if he himself now sees it as folly. The explosion at the court house is indicative of this new ideology’s rejection of establishment institutions, highlighting their dystopic vision of a new America. Trump parallels continue to abound.

Folie à Deux is a psychiatric condition where two people with mental illness are enmeshed together who begin to share the same psychotic delusions about the world. While it is assumed that Harley Quinn is the second ill person in this dyad, she is only an individualized symbol of the broader delusional support for Joker’s Robespierrean justice; the delusion that this savagery is a worthwhile response to systemic oppression. They are all of them enmeshed into this cult of vengeful destruction.

This is why the second film is not a rejection of the first. It does what any sequel is supposed to do and expands on the themes of the first one. Joker’s Trumpian philosophy has broadened in appeal, and regardless of its instigator’s opinions, it will continue without him. Trump’s chaos is here to stay. The film is also just as ambiguous of its support for this ideology as the first one. The singing in the film is an obvious metaphor for the mania that drives Joker’s methods. In the end when Arthur confronts Harley (I refuse to call her Lee), he asks her to stop singing, to come back to earth, and she refuses. Whether the singing was any good or not is irrelevant; singing is always more fun! Joker’s revolution, however violent, however cruel, has a mischievous joy to it. The memes about cats and dogs in Springfield, Ohio are fun, and who cares about any school children who receive bomb threats along the way?

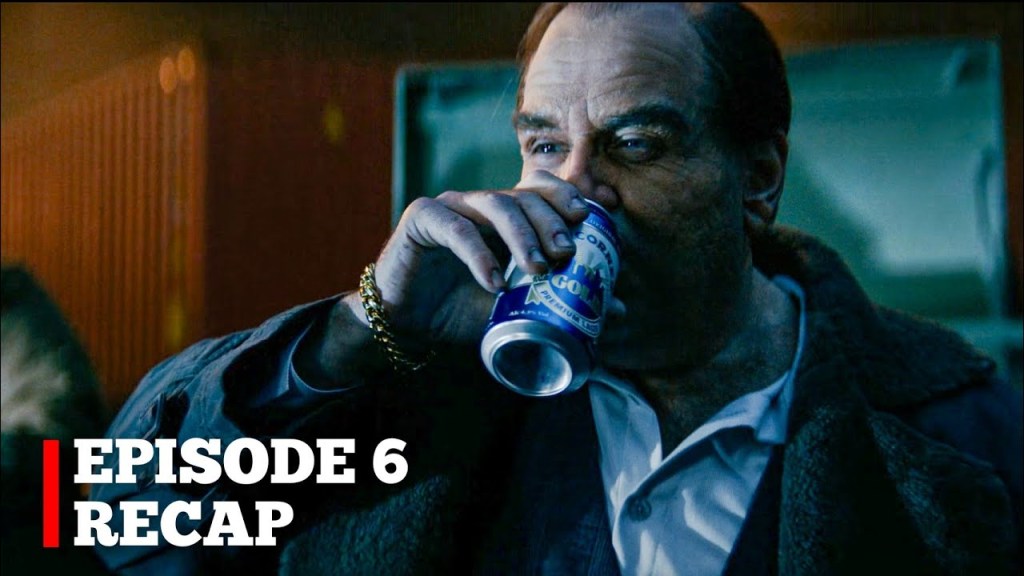

The Penguin begins his own journey along more antiheroic tropes. He is an underdog, and while it’s clear that his lies are ubiquitous and sociopathic from the beginning, we root for him because he comes from a similar background to Arthur. He’s easy to applaud as the antithesis to the opulence of the Falcone family. He’s dirty in a way that poverty dirties everyone it touches; his grimier aspects are not something our modernity rejects, but something it connects to and empathizes with as we too scrounge in the dirt in envy of the wealthy. Oswald also loves his mother and takes as his ward the young Victor, allegedly sharing a journey to transcend their lot as all of us yearn to. He could easily have been a nuanced hero.

But Oswald Cobb(lepot) is a villain. He murders his brothers. He murders his ward. He feels nothing for other people, even the ones he’s convinced us he does. He keeps his mother alive in her vegetative state despite her wishes in order to fulfill the dream that he has projected onto her. It’s always been his dream, not hers. The Penguin does not understand how to connect to other people, only how to fake it well enough for the cameras. We are comfortingly assured otherwise because he is a very convincing grifter, and the pathway to power that he sees as the most efficient is the one where he aligns himself with the working class. There is not a single revolutionary bone in his body, only frigid calculus. His populist deed to restore power to Crown Point was done only for his own ends and adjacent benefits toward others were not considered; Victor’s enthusiastic gratitude appears to genuinely confuse him before he catches himself and finds a way to take advantage of that edge. There is no ambiguity to The Penguin. He is clearly an unapologetic monster, and Sophia Falcone’s sarcastic scoff at him being a Man of the People is illuminating in how obvious it is in its falsehood.

Where Joker is a representation of Trumpism and its followers, The Penguin is emblematic of the man himself. Trump was certainly never working class, nor has he had to work hard to elevate himself above his station, but the sociopathic exploitation of working class consciousness to raise himself to grotesque power is clear. Oswald Cobblepot in the comics is an established elite, as wealthy as Bruce Wayne, but he doesn’t need to be in the show to be comparable to the president-elect because his methods are identical, regardless of his background. A grifter by any other pedigree would sound as sweet. In a broken world, the Penguin takes advantage in a way that people are desperate for. They want him to be what he’s pretending to be because they see his elevation as their own. If Oswald wins, then Victor wins – the grift only becoming obvious when the life is strangled out of him. Trump’s own escalating lies put Penguin’s to shame, but despite their obvious contradiction to reality, people cling to them as a life preserver on a sinking ship. The delusion of his proffered transcendence is a siren’s song. But they are villains; they’re both only in it for themselves.

Villainy has certainly evolved over time. Nowadays, damsels can manage their own distress, and devils only exist in fantasy. But monsters still exist, and understanding our world means understanding the monsters that it creates. We live under the exploitation of the elites. We are, as individuals, powerless to stop them. How will we choose to respond to this? Will we gaze too long into the abyss and become monsters ourselves? Or will we settle into passive reverence at the feet of the devil, spellbound by his honeyed lies?

How do we resist in a world without heroes?